The escalating conflict between the Chief Minister and the Lieutenant Governor raises several constitutional and legal issues on the scope and extent of their powers in the National Capital Territory (NCT) of Delhi. The tussle over control of key bureaucratic appointments, was sparked by the LG’s appointment of IAS officer Ms. Shakuntala Gamlin as acting Chief Secretary, which was opposed by the representative democratic government on grounds that it fell beyond the scope of the LG’s powers to do so without the aid and advice of the Council of Ministers (CoM). Adding to this conundrum was the Delhi High Court’s ruling in Anil Kumar V. GNCT of Delhi, holding that the Home Ministry notification, which indirectly expanded Centre’s powers in the region, was ‘suspect’. Although the dispute is coloured by highly partisan political contestations, the issue is more a matter of constitutional and statutory interpretation.

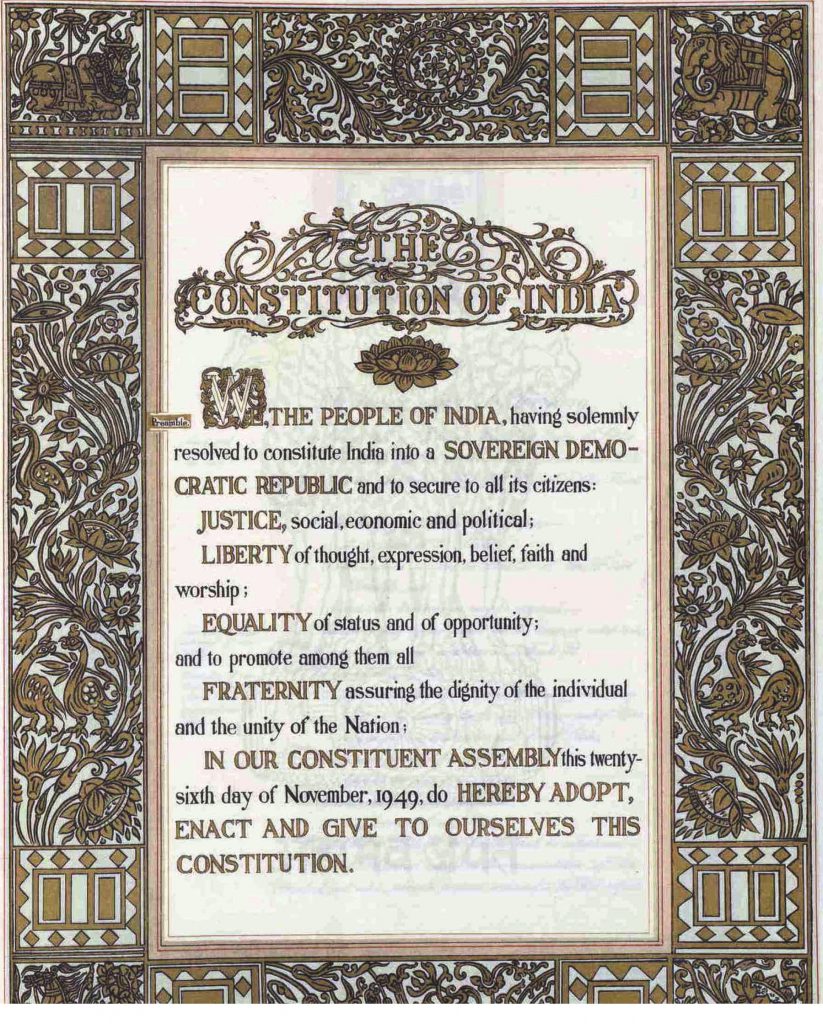

Historically, Delhi was administered by a Chief Commissioner and after a few changes the Metropolitan Council was set up in 1966 which was empowered to deliberate and recommend but not legislate. Delhi is classified as a Union Territory in Schedule I of the Constitution, yet it is not governed by Article 239AA (as against Article 239 which covers Union Territories in general). The other laws relevant to understanding evolutionary quasi status of Delhi are the Government of National Capital Territory of Delhi Act, 1991 (GNCT Act), the rules formulated under this Act (Transaction of Business Rules), and the related judicial pronouncements. It is needless to say that the precise contours of the sharing of powers between the LG and the Delhi Government are a grey area. However, on a reading of the pertinent Article 239AA(4) a reasonable case may be made to clearly suggest that firstly, the LG will have to take decisions based only on the “aid and advice” of the Council in exercise of all matters on which the Legislative Assembly has power to make laws; secondly and consequently the legislative assembly of Delhi has power to make laws on all matters enumerated in the State List and the Concurrent List in the VII Schedule of the Constitution, except entries related to public order, police and land. [Article 239AA(3)]; thirdly for all other matters, the LG can act in his own discretion but only when there is a specific law conferring this discretion on him and fourthly all disputes between the LG and the CoM shall be referred to the President.

There is no such law granting discretion to the Lieutenant Governor for making such appointments currently. Thence, the crucial question is what is the nature of the “aid and advice” that the CoM gives the LG. If the advice is binding, then the LG cannot make unilateral appointments to such posts. The reasoning for this assertion can be found in the Apex Court’s landmark judgement of E.P. Royappa V. State of Tamil Nadu which states that the post of Chief Secretary is a highly sensitive post, a lynchpin in the administration, therefore, smooth functioning of the administration requires that there should be complete rapport and understanding between the Chief Secretary and the Chief Minister. Furthermore, on a reading of Devji Vallabhbhai Tandel V. Administrator of Goa, where the Supreme Court held that the Administrator of a UT is never bound by the advice of his CoM, and the disagreement has to be referred to the President for his decision, it can be argued that the LG is not bound by the aid and advice of the CoM.

Interestingly, both the intrepretations do not hold the ground since Delhi is a peculiar case, neither being a State, nor a Union Territory. The Supreme Court in NDMC V. State of Punjab observed that Delhi is an evolving Union Territory with trappings of a State, thus raising several constitutional conundrums. Therefore, Article 239AA can be viewed as a badly framed provision precisely because it highlights a constitutional anomaly about Delhi.

Significantly, it also needs to be seen that the Constitutional Amendment and the GNCT Act, 1991, were not passed in isolation. They emanate from the well-recognised principle of inherent diarchy. Thus, demands for full statehood or greater central control are both untenable. Firstly, as the national capital, the Union government has the responsibility for the city’s orderly growth and security. Also, sensitive areas like foreign missions, the areas of national significance (eg. Red Fort) and some others can be administered by continuing with the Central government exercising powers of oversight. In comparison with global capitals such as Washington, D.C. and Canberra are “federally administered territories” where legislative actions of the city are subject to approval by the Congress, their finances have federal constraints and their Budget is approved by the President.

Conclusively, to do away with vague and murky existing laws which lack clarity, a strong case can be made for rewriting of laws rather than reinterpretation of laws, with the Apex Court’s impending consideration of the notification. Another instance of vagueness in the law governing Delhi is in the treatment of its police. The recent dispute over powers and jurisdiction of Anti-Corruption Branch (ACB) brings light to this confusion. If the Delhi government has no control over its police, then Entry 2 of the Concurrent list has no meaning. The lack of clarity is evident because the ACB can be excluded from Delhi Government’s scope by invoking the entry on ‘Police’ in State List, and it can brought within the scope of the government by invoking the entry of ‘Criminal Procedure’ under Concurrent list.

The moot point being made that since the Capital represents an entire nation and as home to the National Government symbolizes national interest, therefore a fine balance has to struck also taking into consideration that Delhiites claim for the right of self-government enjoyed by their compatriots.